GRAMMAR COMMENTARY

11.1. Text Division Techniques

When reading pre-classical Chinese texts, we constantly face a problem that rarely arose when studying Yin inscriptions. This involves dividing the text and defining sentence boundaries.

For this purpose, several specific techniques can be used with Zhou texts. Of course, not every one of them can be applied in every case.

The basis for dividing a text into sentences is our knowledge of the structure of the ancient Chinese sentence. The same sentence parts exist in the pre-classical language as in the archaic language, and they occupy the same positions as before. Therefore, it can be argued that, for example, after a predicate and a direct object, only an indirect object with a preposition can follow, and after that, the presence of any other sentence part is impossible. Thus, if we determine the presence of an indirect object with a preposition in postposition relative to the predicate, this indicates the end of the sentence.

Further, although Zhou inscriptions are not as standardized in their formula as Yin inscriptions, they also contain some familiar formulas, knowledge of which allows us to break the text into smaller parts.

For example, almost every inscription contains words addressed by the king or another high-ranking official to the owner of the vessel. These words are usually given as direct speech, i.e., introduced by the word 曰 yuē, and begin with an address. The king's speech in such cases begins with the words: 王若曰 wáng ruò yuē "The king said: ‘...”".

The wang's speech is usually followed by a phrase in which the owner of the vessel expresses gratitude for the award, favor, or other recognition of his services. This phrase can take various forms, most often as follows:

...拜手稽首對揚...休 ...bài shǒu qǐ shǒu duì yáng ... xiū

"...folded his hands and bowed to the ground, made an inscription [on the vessel and thereby] offered praise... for [his] mercy."

The following is a message stating that the owner of the vessel dedicates it to the memory of an ancestor:

用作...尊彝 yòng zuò...zūn yí "Used it as a sacrificial vessel..."

11.2. The Personal Pronoun 厥 jué

The personal pronoun system of the archaic period was characterized, as already mentioned, by a clear contrast between one group of personal pronouns used as subjects and objects, and another group (as noun modifiers).

This distinction persists in the early preclassical language.

First-person pronouns (余 yú for the 1st person, 汝 rǔ for the 2nd):

a) subject pronouns:

余唯令 yú wéi lìng "I command";

汝勿不善 rǔ wù bù shàn "You should not do wrong";

b) object pronouns:

受余 shòu yú "grant to me";

令汝 lìng rǔ "to command you."

Second-person pronouns (朕 zhèn for the 1st person, 乃 năi for the 2nd):

拼朕位 pīn zhèn wèi "Support my throne!"

乃祖既令乃父 năi zǔ jì lìng năi fù "Your grandfather commanded your father."

However, if the archaic language was completely devoid of any third-person pronouns, then in the texts of the early pre-classical period, 厥 jué appears - a new personal pronoun belonging to the second group.

The specific usage of this pronoun is evident, for example, from the following two passages, one of which contains direct speech and the other does not:

令曰更乃祖考 lìng yuē gēng năi zǔ kăo "He ordered: 'Take the place of your grandfather and father!'"

令更厥祖考 lìng gèng jué zǔ kăo "He ordered: 'Take the place of his grandfather and father.'"

厥 jué is a third-person personal pronoun used only as an attribute of a noun. This means that in the text, only a name can follow this pronoun:

厥絲束 jué sī shù "his skein of silk";

厥寶尊彝 jué băo zūn yí "his precious vessel."

厥 jué can be translated as "his":

公賜厥順子貝 gōng cì jué shùn zǐ bèi "Gong gave his obedient son shells."

11.3. Doubling of Notional Words

Several different cases of doubling notional words are found in pre-classical Chinese.

One of these is doubling a word in a nominal function. It is used to denote a plurality of objects (persons) expressed by a given name:

子子孫孫 zǐ zǐ sūn sūn "children and grandchildren."

11.4. Adverbial modifiers of action duration

In pre-classical (as well as archaic) language, an indication of the duration of an action or state is expressed by an adverbial modifier preceding the corresponding predicate:

三年静東國 sān nián jìng dōng guó "He pacified the eastern states for three years."

Inscriptions on Western Zhou bronze vessels often use standard formulas to indicate duration of action, including the phrase 萬年 wàn nián "ten thousand years":

余其萬年寶用 yú qí wàn nián băo yòng "I will treasure [this vessel] for ten thousand years."

效其萬年奔走扬公休 xiào qí wàn nián bēn zǒu yáng gōng xiū "Xiao will try to repay the gong for his favor for ten thousand years."

The fact that this phrase is used here specifically as a circumstance is indicated by the adverb 其 qí preceding it.

The presence of the adverbs 亦 yì and 其 qí before the noun phrase 子子孫孫 zǐ zǐ sūn sūn allows us to determine that it is also an adverbial modifier in the following sentence:

亦其子子孫孫永寳 yì qí zǐ zǐ sūn sūn yǒng băo "And [this vessel] will also be used as a treasure forever, throughout the lives of all sons and grandsons."

LEXICAL COMMENTARY

11.A. Date Designations

The system of cyclic signs continues to be used to designate days in Zhou time, as in Yin time. However, in general, dates are now written somewhat differently.

First of all, the word 年 nián is used to designate the year, which previously meant "harvest." It is usually preceded by the word 王 wáng, indicating the system of chronology adopted by the Zhou ruler. However, the title of wang is not indicated, and it remains unknown which ruler is meant (there was no unified calendar system during the Zhou period).

The year designation is usually followed by the corresponding month. The first month of the year is called 正月 zhēng yuè, and subsequent months are designated by the phrases 二月 èr yuè "second month," 三月 sān yuè "third month," etc.

The day designation is sometimes preceded by the expression 辰在 chén zài "the constellation is in...," related to the peculiarities of Zhou astronomical beliefs.

The date at the beginning of the inscription is always marked with the emphatic particle 唯 wéi:

唯王二十又五年四月甲午 wéi wáng èr shí yòu wǔ nián sì yuè jiă wǔ "the twenty-fifth year of Wang, the fourth month, the day of Jia-wu."

11.B. Designating the Time of Day

Yin inscriptions contain several special terms for designating parts of the day: 明 míng "dawn," 旦 dàn "sunrise," 朝 zhāo "morning," 中日 zhōng rì "noon," 昏 hūn "evening," 夕 xī "night." The Zhou people divided the day in almost the same way. The only innovation, perhaps, was the identification of another period—the time before dawn, when the night was already drawing to an end. This time was called 昧爽 mèi shuăng or 昧旦 mèi dàn (the Shijing contains the following phrase: 女曰雞鳴, 士曰昧旦 nǚ yuē jī míng, shì yuē mèi dàn "The wife said: 'The rooster has crowed,' the husband said: 'The darkness is thinning.'").

Note that all the ceremonies associated with the appointment of high-ranking officials, etc., always began very early, often before dawn, so that their most important part would occur at the moment when the sun rose.

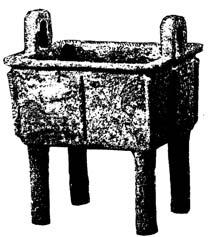

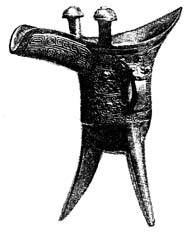

11.B. Zhou Ritual Vessels

Before their conquest, the Zhou apparently did not possess bronze casting technology. After conquering Yin, they recruited Yin artisans into their service, and therefore early Zhou bronzes, including ritual vessels, are generally similar to their Yin prototypes.

Sacrificial offerings during the Zhou period used several types of vessels, each with a different purpose.

Meat was boiled in tripods or tetrapods called 鼎 dǐng, and grain in 鬲 lì. The cooked food was placed in a 簋 guǐ vessel—a round vessel on a low tray. Wine libations were an essential part of any sacrifice. Wine was poured into vessels of various shapes, the most important of which were lidded jugs with an arched handle, 卣 yǒu. Wine was drunk from goblets called 爵 jué.