GRAMMAR COMMENTARY

13.1. Tense-aspect markers (continued)

Besides the marker for the beginning of an action 肇 zhào, discussed in the previous lesson, there are other function words of the same class in the pre-classical language.

One of them, 既 jì, indicates the completion of an action. The meaning of 既 jì is very close to the meaning of the perfect tenses in English. It does not correspond to any specific time. This marker merely emphasizes that the action has already been completed in the past or will be completed in the future. In this sense, 既 jì is contrasted with 肇 zhào, which denotes the beginning, and therefore the incompleteness, of an action.

Compare: 汝肇誨于戎工 rǔ zhào huì yú róng gōng "You have only just begun to penetrate the secrets of the art of war." 余既令汝 yú jì lìng rǔ "I have already ordered you."

13.2. Nominal Tense Markers

Aspect-tense markers in predicatives should not be confused with a group of words denoting a relative moment in time and functioning as a noun. Two words from this group have already been encountered in archaic texts. These are 今 jīn "now" and 昔 xī "earlier," "in the past."

In pre-classical Chinese, the system of notations for relative moments in time becomes more complex. A special notation is given to the moment preceding 昔 xī, corresponding to the English "long ago," "once upon a time." It is expressed by the word 載 zài: 載先王既令乃祖考, 今余唯帥型先王令 zài xiān wáng jì lìng nǎi zǔ kǎo, jīn yú wéi shuài xíng xiān wáng lìng “The once deceased Wang already ordered your ancestors, now I take the order of the late Wang as a model.”

Apparently, in the context of the Zhou inscriptions, the period referred to as 昔 xī refers to the reign of the previous king, while 載 zài refers to an earlier period.

13.3. The Negation of 非 fēi

In the Early Preclassical language, along with the previous negations 不 bù, 弗 fú, 勿 wù, a new word of the same category appears—非 fēi. In its properties, it is similar to a neutral negation: 非出五夫 fēi chū wǔ fū "not to hand over five people."

13.4. Counters

In the archaic language, when denoting quantities, in addition to duplicate names (人十人 rén shí rén "ten people", 羌五羌 qiāng wǔ qiāng "five qiang"), only units of counting denoting the measure of the volume of small objects or substances are used.

Counting constructions of these two types are also found in Western Zhou texts:

a) 人萬三千八十一人 rén wàn sān qiān bā shí yī rén "13,081 people";

聝百三十七聝 guó bǎi sān shí qī guó "137 cut off ears";

b) 鬯一卣 chàng yī yǒu "one jug of wine";

矢五束 shī wǔ shù "five bunches of arrows".

One of the manifestations of the development of the ancient Chinese language during this period was the emergence of counters in the proper sense of the word, used to count individual objects and not coinciding with the corresponding names.

Thus, the word 匹 pǐ becomes a counter for horses: 馬百四匹 mǎ bǎi sì pǐ "104 horses"; for people - 夫 fū: 人鬲自御至于庶人六百又五十又九夫 rén lì zì yù zhì yú shù rén liù bǎi yòu wǔ shí yòu jiǔ fū “659 dependent people, starting with grooms and ending with common farmers”; for chariots — 兩 liàng (in the Yin Dynasty, this word was used to mean "a pair of horses," "a team"): 車三十兩 jū sān shí liàng "30 chariots."

If a counter is placed before a noun without a numeral, it is assumed that the unit has been omitted: 馬一匹絲一束 mǎ yī pǐ sī yī shù or 馬匹絲束 mǎ pǐ sī shù — "1 horse and 1 skein of silk."

LEXICAL COMMENTARY

13.A. Date Designation (continued)

An innovation in the Zhou dating system was the division of the month into several time periods.

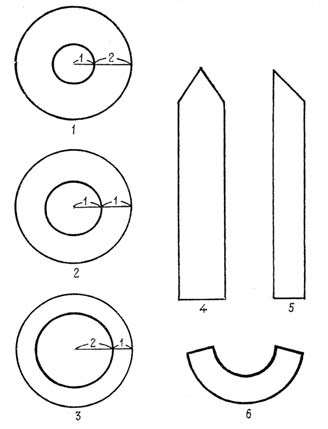

The renowned Chinese researcher Wang Guowei once proposed that there were four such periods. Based on data from the Shangshu and inscriptions on bronze vessels, he believed that the first period was called 初吉 chū jí, the second - 既生霸 jì shēng bà, the third - 既望 jì wàng, and the fourth - 既死霸 jì sǐ bà. According to Wang Guowei, each of these comprised 7 or 8 days (thus, the first period spanned from the 1st to the 7th-8th of each month, the second from the 8th-9th to the 14th-15th, the third from the 15th-16th to the 22nd-23rd, and the fourth from the 23rd to the end of the month).

Later, a different viewpoint was formulated, according to which each month, consisting of 29-30 days, was divided into three periods in Zhou time. This division was necessary because, within a single month, days with the same decimal signs appeared three times. Accordingly, the first 10 days of the month were called 既生霸 jì shēng bà, the second - 既望 jì wàng, and the third - 既死霸 jì sǐ bà. As for 初吉 chū jí, this phrase did not designate a division of the month, but meant "the first lucky day" (followed by the designation of the day): the Zhou people considered all days of the first ten-day period to be auspicious.

This interpretation seems convincing. It is also supported by the etymology of the names of the ten-day periods: 既生霸 jì shēng bà "the moonlight has already appeared"; 既望 jì wàng "[the moonlight] has already become bright"; 既死霸 jì sǐ bà "the moonlight has already dimmed".

Note that in the first and third expressions, the noun 霸 bà "moonlight" is not the subject, but the direct object of the predicates 生 "to give birth" and 死 "to make less bright"; however, in English, it is difficult to find equivalents that grammatically accurately reflect the structure of these phrases.

13.B. Palace Layout and the Investiture Ceremony

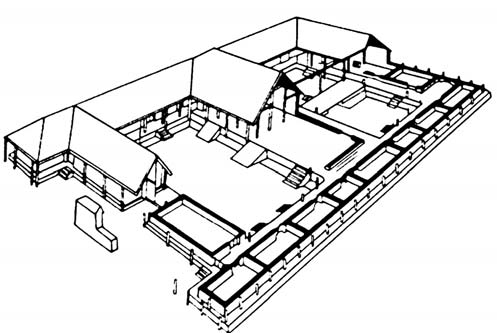

Inscriptions often contain descriptions of investiture ceremonies (granting awards, orders, appointments, etc.). During the Zhou period, such ceremonies were conducted according to a strictly defined ritual. To understand it, it is necessary to understand the setting in which they took place.

Palace buildings during the Zhou period were strictly oriented to the cardinal directions, so the main entrance always faced south and was therefore called 南門 nán mén "southern gate."

Upon entering the main gate, one entered a courtyard called the "great" 大廷 dà tíng. It housed the ancestral temple 大廟 dà miào, and beyond it another gate (二門 èr mén "second gate") leading to the next, or "middle," courtyard (中廷 zhōng tíng). On the opposite side of the middle courtyard was the palace itself, usually called the "big" 大室 dà shì.

The investiture ceremony typically took place in the middle courtyard. The king was in the palace hall and therefore faced south (hence the ancient expression 南面 nán miàn "to face south," i.e., to rule, to be a ruler).

The dignitary escorting (右 yòu) the person being invested entered the courtyard through the second gate. They stopped before the steps leading to the palace hall, facing the king, i.e., north.