GRAMMAR COMMENTARY

45.1. A special case of the function word 皆 jiē

Above (38.7) it was noted that the function word 皆 jiē comes after the subject and indicates that all objects or persons expressed by the subject perform the action indicated by the predicate.

A special case of the function word 皆 jiē is that the latter can refer not to the subject, but to a prepositional object. In any case, 皆 jiē always comes after the word with which it is semantically related and precedes the predicate: 士皆謙而禮交之 shì jiē qiān ér lǐ jiāo zhī "He was modest toward all his subordinates and communicated with them in accordance with the rules of etiquette" (the forward object is duplicated here by the pronoun 之 zhī).

45.2. A construction with the predicative 無 wú

If the predicative 無 wú is followed by two antonymous nouns, then

the entire construction has the meaning "whether... or," "both... and," for example: 士無賢不肖 shì wú xián bù xiāo "people—both wise and foolish."

45.3. The Functional Word 當 dāng (continued)

Besides the fact that 當 dāng is used in classical Chinese as a modal predicative (44.4), it is often used to

form an adverbial modifier of time. Apparently, 當 dāng can be considered as a preposition introducing both nominal and predicative phrases: 當在宋也予將有遠行 dāng zài sòng yě yú jiāng yǒu yuǎn xíng “When I was in Song, I intended to undertake a long journey.”

But the most common adverbial modifier of time includes the construction 當...時 dāng... shí (it always stands only at the beginning of a sentence): 當是時諸侯以公子賢多客不敢加兵謀魏 dāng shì shí

zhū hóu yǐ gōng zǐ xián duō kè bù gǎn jiā bīng móu wèi “At that

time, the Zhuhou did not dare to send troops and plot anything against Wei, because the [Wei] ruler’s son was wise and had many freeloading guests.”

當此之時寇賊並起 dāng cǐ zhī shí kòu zéi bìng qǐ "At that time, bandits appeared here and there."

In connection with the last example, note that the demonstrative pronoun 此 cǐ "this" is attached to the object defined by the function word 之 zhī—a phenomenon not observed until the late classical period.

45.4. The adversative conjunction 然 rán

The word 然 rán can be used in classical Chinese as an adversative conjunction, forming a sentence that contains a message contradicting the preceding one. Corresponds

to the English "but", "and nevertheless", etc.: 衛青霍去病亦以外戚貴幸,然頗用才能自進 wèi qīng huò qù bìng yì yǐ wài qì guì xìng, rán pō yòng cái néng zì jìn "Wei Qing and Huo Qubing also enjoyed the emperor's favor because they were his female relatives, but they rose to prominence largely thanks to their abilities."吾嘗將百萬軍,然安知獄吏之貴乎 wú cháng jiāng bǎi wàn jūn, rán ān zhī yù lì zhī guì hū “I have commanded an army of a million, but how could I have known

then how high a rank a jailer occupies?” The adversative conjunction 然 rán is often combined with 雖 suī "although": 荊軻雖遊酒人乎,然其為人沈深好書 j īng kē suī yóu

jiǔ rén hū, rán qí wéi rén shěn shēn hào shū "Although Jing Ke associated with drunkards, he was balanced by nature

and had a penchant for reading books."

45.5. The function word 愈 yù

When it is necessary to show that a particular property or state

is expressed at a given moment more intensely than previously, the function word 愈 yù is used in classical Chinese:

錯以此愈貴 cuò yǐ cǐ yù guì "Because of this, [Chao] Tso occupied an even higher position."

人有畏影惡跡而去之走者,舉足愈數而跡愈多 rén

yǒu wèi yǐng è j ī ér qù zhī zǒu zhě, jú zú yù shù ér j ī yù duō "There was a man who was afraid of his shadow, who disliked his

footprints and ran to get rid of them. But the more often he moved his feet, the more footprints there were."

In the last sentence, the repetition of the function word 愈 yù before the two predicates conveys a meaning corresponding to the English expression "than... that."

LEXICAL COMMENTARY

45.A. Prince Wuji of Wei

The youngest son of the Wei ruler Zhao Wang, named Wuji,

was the half-brother of King Anli Wang (276–243 BC), during whose reign he distinguished himself as a major statesman. Wuji was granted the title of Xinling Jun.

Like most aristocrats of the time, Wuji kept a large number of "guests" in his house, on whom he could rely in times of need. Historical legends portray him as a man who valued sincerity of feelings and disdained the outward manifestations of his very high social status.

45.B. Guard at the Yimen Gate

Large cities of the Spring and Autumn Period typically had several gates, each with its own name. The capital of the Zhou king, for example, had 12 gates.

The gates were closed at night. Therefore, special guards were assigned to them, opening the gates in the morning and locking them in the evening.

45.B. The Hermit Hou Ying

The word 隱士 yǐn shì, later used to mean "hermit," had a slightly different meaning during the Zhangguo era. It was used to describe individuals who possessed abilities and high human qualities, but for one reason or another did not serve the ruler, and if they did hold any positions, they were insignificant and completely inappropriate. Such a person was, for example, a certain Hou Ying, a guard at the Yimen Gate in the capital of the Wei Kingdom.

45.G. Seating a Guest on the Left

The seat of honor (上坐 shàng zuò) in ancient China was on the right side of the host, so the person sitting to the right of the ruler was his

"right-hand man." However, on a chariot, the ratio of seats was reversed: the left seat was considered honorable. Xinling-jun, when he went to fetch Hou Ying, left the left seat in his carriage empty, thus showing him his respect.

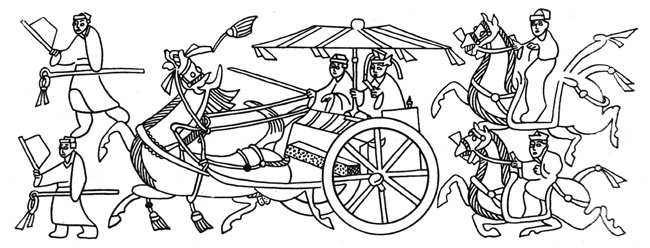

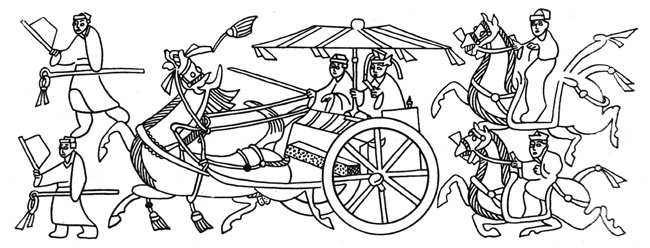

45.D. The Chariot and Riders

Unlike Yin and early Zhou chariots, in which riders stood, chariots of the Zhanguo period were seated, not standing. An aristocrat leaving home usually took several horsemen with him to accompany the carriage.

An Aristocrat's Departure (Ancient Chinese Bas-Relief)