GRAMMAR COMMENTARY

6.1. The notional word 有 yǒu "to have"

The notional word 有 yǒu occurs in texts of the archaic period exclusively in a predicative function. The predicate expressed by this word has two characteristics.

First, it usually has a direct object:

黍年有足雨 shǔ nián yǒu zú yǔ "Will the millet harvest have enough rain?"

Second, instead of a negative predicative, the word 亡 wú "not to have" is used:

旬有禍 xún yǒu huò "Will there be misfortune during the ten-day period?"

旬亡禍 xún wú huò "Will there be no misfortune during the ten-day period?"

The predicate expressed by the words 有 yǒu or 亡 wú is used primarily in cases where it is necessary to emphasize that the subject is not the subject of an action, but, on the contrary, is in a state caused by some action:

西土其有降熯 xī tǔ qí yǒu jiàng hàn "Has drought been sent down to the western lands?" (lit. "Have drought been sent down to the western lands?")

6.2. Preposition 及 jí

The word 及 jí is also an archaic preposition.

This preposition comes from the semantic word "to reach," "to catch up," and corresponds to the English "when will..." or "to...":

及三月雨 jí sān yuè yǔ "Will there be rain by the third moon?"

6.3. The conjunction 眔 dà

A coordinating conjunction between two or more nouns is often unformed (for example: 今來歳 jīn lái suì "the present and next year"). But in archaic Old Chinese, there is also a special function word that formally indicates the coordinating relationship between names. This is the conjunction 眔 dà:

\[

\left.

\begin{array}{c}

\text{羊牛} \quad yáng\ niú \\

\text{羊眔牛} \quad yáng\ dà\ niú

\end{array}

\right\}

\text{ "rams and oxen"}

\]

${data.meaning}

LEXICAL COMMENTARY

6.A. "The Mission of the Wang"

While governing the subject tribes, the Yin Wang simultaneously relied on them in his policy towards his opponents. When setting out on a campaign against a hostile tribe, the king would typically order the militia of "many hou" to be placed at his disposal. Sometimes, however, he would commission a particular leader to act in his name—to carry out a punitive expedition against neighbors, to deliver trophies and prisoners to the Yin capital, etc.

In these cases, the leader of a subject tribe authorized by the ruler was called his "ambassador" (使 shǐ). The same term was used to designate the mission received by the ambassador—the "mission of the king" (王使 wáng shǐ).

6.B. "Punitive Campaign"

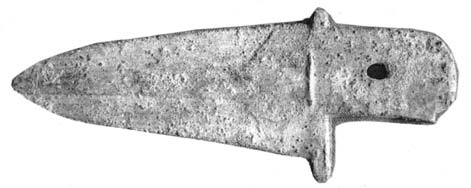

The ancient Chinese asserted that "the main affairs of the state are war and sacrifice." Fortune-telling inscriptions are a vivid illustration of this postulate. The Yin people used various names for military expeditions against hostile tribes, but the primary term for "punitive expedition" was 伐 fá. It was written with an ideogram depicting a man with a pickaxe pressed to his neck—the primary stabbing and cutting weapon of the time.

Pickaxes were made of bronze and mounted on a long wooden handle. This weapon could be used to decapitate an enemy without allowing them to get close.

On the left is a bronze pickaxe tip; on the right is the ancient inscription of the character "伐 fá."